MUCH interest was excited by the arrival in Havana of the first lot of American newspapers received after the loss of the Maine. A Spanish officer of high rank whom I visited showed me a New York paper of February 17 in which was pictured the Maine anchored over a mine. On another page was a plan showing wires leading from the Maine to the shore. The officer asked me what I thought of that. It was explained that we had no censorship in the United States; that each person applied his own criticism to what he saw and read in the papers. Apparently the Spanish officer could not grasp the idea. The interview was not at all unfriendly, and he took it in good part when it was pointed out that the Havana newspapers were very unfair toward me, without respect to my situation in their port. I asserted that if the American newspapers gave more than the news, the Spanish newspapers gave less than the news: it was a question of choice.

When the Spanish officer reverted to those illustrations of the Maine, I argued in this wise: The Maine blew up at 9:40 P.M. on the 15th; the news reached the United States very early on the morning of the 16th. This newspaper went to press about 3 A.M. on the morning of the 17th. It took time to draw those pictures and reproduce them. The inference was clear: the newspaper must have been possessed of a knowledge of the mine before the Maine was blown up. Therefore it disturbed me to guess why I had not been told of the danger. This had the required effect, and the newspaper was dropped out of the conversation.

The American newspaper correspondent in Havana was a bugaboo to the Spaniards, from the censor to others all along the line. Nobody but the censor seemed to be able to stop him, and even the censor could not control more than the cable despatches. I remember that one correspondent complained that he was not allowed to say that Captain Sigsbee was reticent. He was made to say that Captain Sigsbee was reserved. The censor thought it a question of courtesy. The correspondents were active, energetic, and even aggressive in their efforts to get all the news. The people of the United States demanded the news, and they got it. It was soon plain to me that the correspondents were under strict orders from their papers -- orders more mandatory and difficult of execution than those commonly issued in the naval service. Very early I applied a certain rule of conduct to these gentlemen, and it worked to perfection. I never impugned their motives, nor denied myself to them when it was possible to see them, never misled them, nor gave any one correspondent the" start in the running." If I had news that could properly be given, I gave it. If what I knew could not be given, I so informed them frankly. I could not give "interviews." My acquaintanceship extended to every American correspondent in Havana. No more sincere sympathy, consideration, and forbearance were shown me than by these correspondents. During the sittings of the court of inquiry, when I could not properly converse on the subject of the investigations, I gave them no word of news, which they were under extreme pressure to provide. . Their approval in the matter was expressed both sentimentally and tangibly when I was leaving Havana, of which more later.

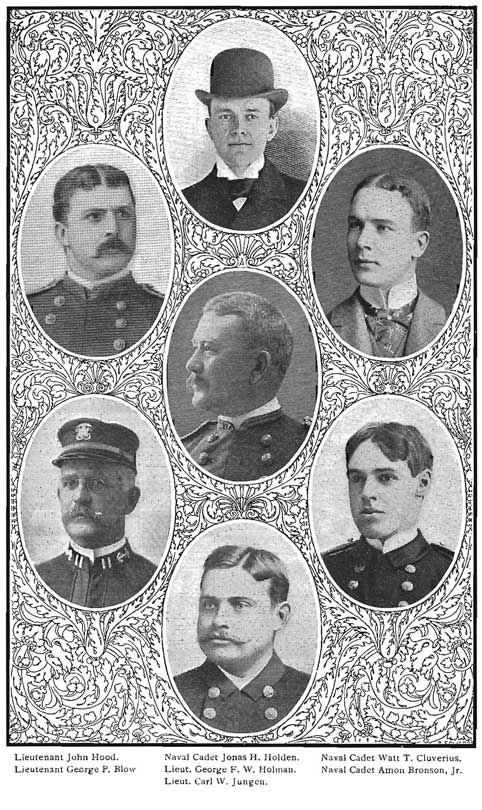

Every mail brought me many letters from the United States and abroad. In the aggregate there were hundreds of them. More than half were letters of approval and commendation. Many were from the families of the dead and wounded men. The latter were answered at once; the former so far as opportunity permitted, but many remain unanswered because of the constant emergency, both great and small, that has pressed upon me since the loss of the Maine. I read every letter from mourning relatives, but the harrowing nature of their contents made it absolutely impossible for me to answer them personally, burdened as I was by urgent and unwonted duties. It was touching to note that most of them contained apologies for appealing to me while I was pressed with other duties. They were indorsed with suitable directions as to writing or telegraphing, and then given over to Chaplain Chidwick and Naval Cadet Holden for reply. From what I have written, it may be inferred that Chaplain Chidwick did this duty thoroughly well. So did Mr. Holden; he was my right hand, in many ways, at Havana, and saved me mutth work and anxiety. His judgment, ability, and sense of duty and loyalty were strikingly admirable. He is one of the best examples of what the Naval Academy can produce when the basic material is of the right kind.

My personal relations with General Blanco and Admiral Manterola, and, in fact, with all the Spanish officials, remained cordial until the last; there was no interruption whatever. Soon after the explosion I received a personal visit from Admiral Manterola at the Hotel Inglaterra. He, was accompanied by his aide, a lieutenant in the Spanish navy. Our interpreter was a very intelligent clerk of the hotel, Mr. Gonzales. Admiral Manterola had ordered an inquiry, on the part of the Spanish government, into the cause of the explosion. We talked freely, because I desired to let it be known that I had no fear of an investigation, and believed that the United States would be impartial.

The admiral assumed from the first that the explosion was from the interior of the vessel. He asked if the dynamo-boilers had not exploded. I told him we had no dynamo-boilers. He said that the plans of the vessel, as published, showed that the guncotton store-room, or magazine, was forward near the zone of the explosion. He was informed that those plans had been changed, and that the guncotton was stowed aft, under the captain's cabin, where the vessel was virtually intact. He pointed out that modern gunpowders were sometimes very unstable. This was met by the remark that our powder was of the old and stable brown prismatic kind, and that we had no fancy powder. He referred to the probable effect of boilers, lighted, near the forward coal-bunkers, which were adjacent to the magazines. This again was met with the remark that for three months no boiler in the forward boiler compartment had been lighted; that while in port the two aftermost boilers in the ship had been doing service.

Apparently Admiral Manterola was not inclined to accept anything but an interior cause. I remarked that our own investigation would be exhaustive, and that every possible interior cause would be included. He seemed desirous of knowing the tendency of my views, and I was equally concerned to know what he thought. . I ventured to say that a few persons of evil disposition, with conveniences at hand, if so inclined, could have blown up the Maine from the outside; that there were bad men everywhere as well as good men. He turned to the interpreter and said something which I could not understand; evidently he did not like that view. I caught enough of the interpreter's protest to him, and also of the aide's, to understand that they advised him to be conciliatory toward me. Their glances were directed toward him to the same effect. I appeared not to observe anything unusual, but went on to say that any investigation which did not consider all possible exterior causes, as well as all possible interior causes, would not be accepted as exhaustive, and that the United States government would not come to any conclusion in advance as to whether the cause was exterior or interior. Admiral Manterola conceded the point very politely, and soon after the visit terminated in the usual friendly way.

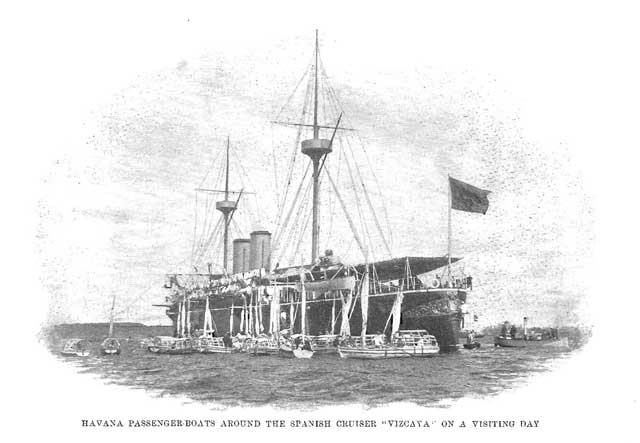

On the afternoon of March 1 there was a great demonstration on the water and along the waterfront. Aerial bombs were thrown up for some hours, and the excitement intensified toward sundown. Shortly after sunset the Spanish armored cruiser Vizcaya arrived from New York. Her entrance excited great enthusiasm among the Spaniards. Many boats and steamers were present to give her welcome. There were streamers and flags flying on shore, and the wharves were crowded with people. It was reported to me that there were cries of "Down with the Americans!" It was different from an American demonstration; it was. childlike, even pathetic. Lieutenant-Commander Cowles of the Fern and I went on shore in the thick of the crowd, and, pressing through the narrow gateway leading from the Machina to the city streets, pursued our way quite as usual. After the arrival of the Vizcaya Americans at Havana remained serene in the knowledge of that fine fleet over at Tortugas. The Maine was a thing of the past, but the fleet was a thing of the future. By that time the atmosphere at Havana was waxing volcanic with the promise of war, but the Spaniards apparently gave no heed to our fleet, which could then have destroyed Havana in short order.

Lieutenant-Commander Cowles, as the junior in rank, made the first visit of ceremony to Captain Eulate of the Vizcaya, and informed him that I was quartered on board the Fern. Captain Eulate then visited me on board. I was in citizen's clothes, having lost all my uniforms. A seaman of the Fern interpreted for us. Captain Eulate addressed himself chiefly to Lieutenant Commander Cowles until the interpreter chanced to mention my name, when Captain Eulate turned in surprise and asked if I was Captain Sigsbee of the Maine. He took in the situation at once, arose, and, with an exclamation, threw his arms about me and gave expression to his sympathy. He afterward spoke pleasantly of his rather extensive acquaintance with United States naval officers.

On March 5 the Spanish armored cruiser Almirante Oquendo, a sister ship of the Vizcaya, arrived at Havana amid demonstrations similar to those which had greeted the Vizcaya. Then the Spanish element of the populace was steeped in happiness and contentment. The lost power of the sunken Maine was manifestly exceeded by . that of the Spanish ships. Assuredly there was much reason for their exhibition of pride, for the Spanish cruisers were fine specimens of naval architecture. They were visited day after day by the people of Havana, and were, therefore, almost constantly surrounded by boats during visiting-hours. The two cruisers were much alike. A bead or molding under the coat of arms on the stern was painted black on one and yellow on the other, and this was about as striking a distinction as could be observed. Once when I remarked to Captain Eulate the similarity, he smiled and claimed there was a difference in his favor: the Viecaya had a silk flag and some Galician bagpipers, which the Oquendo had not.

After the arrival of the Vizcaya I was informed that the Fern would soon leave Havana to take food to the reconcentrados in other ports. It was intended that I and others, including the divers, should quarter ourselves aboard the Mangrove. I reported to Rear-Admiral Sicard that the Mangrove had not quarters sufficient for us.. It was necessary to safeguard the health of the divers very carefully; their work in the foul water of the harbor compelled this. It was also pointed out that I would be left without uniformed officers to employ for naval visits and courtesies. Accordingly, the Montgomery, Commander George A. Converse, arrived on March 9, to relieve the Fern, which left the same day. The Montgomery, a handsome and efficient ship, presented a fine appearance from the city.

This relief of vessels gave rise to an incident which, by confusion, has produced the impression, rather wide-spread in the United States, that the Maine's berth was shifted by the Spanish officials after her arrival at Havana. It has already been stated that she remained continuously at the same mooring-buoy. The Fern had been lying at the buoy nearest the Machina and the wreck of the Maine, NO.4 of Chart 307, the same that had served for the Alfonso XII prior to the explosion. In expectation of the arrival of the Montgomery, the Fern had procured a pilot in the forenoon of the 9th. The prospective coming of the Montgomery had been announced to the Spanish officials, and it had been arranged with the pilot that the Montgomery should succeed to the Fern's buoy. To avoid confusion, the Fern vacated the buoy several hours in advance and rode to her own anchor near the wreck. As soon as she had shifted her berth, a Spanish naval officer, representing the captain of the port, visited the Fern, and informed me that a buoy to the southward of the wreck, No. 6 of Chart 307, would be given to the Montgomery, as the Alfonso XII was under orders from Admiral Manterola to take the moorings vacated by the Fern. I at once sent an officer to Admiral Manterola with a note requesting that the Montgomery be permitted to take the Fern's buoy, in view of its close proximity to the wreck, - if consistent with the necessities of the Spanish ship. The Alfonso XII reached the buoy before the officer reached the admiral. A prompt reply was returned, saying that the change had been made in order that the Spanish cruiser might be near the Machina, which was more convenient for the prosecution of work on her boilers, but that she would be moved back if I so desired. Before I could make known my wishes the Alfonso XII hauled off and took another berth. I then visited Admiral Manterola personally, and requested that the Alfonso XII keep the Fern's buoy, and that I be permitted to anchor the Montgomery where the Fern was then lying. The admiral declined to entertain the proposition, courteously insisting that the Montgomery should have the desired buoy. He stated that the captain of the port had mistaken his orders, or that there had been a misunderstanding of some kind. The Montgomery took the buoy when she arrived later in the day. Frankly, I preferred that buoy for the further reason that it had been used for the Alfonso XII, from which I judged that the berth would be free from harbor-defense mines, if any existed.

I had received no assurance that the harbor was not mined, and was of the opinion that the Maine had been blown up from the outside, irrespective of any attachment of culpability to the Spanish authorities. It had been made sufficiently plain that those authorities were not taking measures to safeguard our vessels. There were two ways of regarding this omission: first, that they believed that there was no need for safeguarding; secondly, that if there was need, they would not, as a question of policy, seem to make the admission. The proceedings of the Spanish commission to investigate the loss of the Maine show that Spanish boats kept a patrol about the floating dry-dock. It would have been mincing matters to infer that I had not the right to act in all proper ways according to any suspicions, just or unjust. The situation in which I found myself was not one to inspire me with perfect trust in my fellow-men. There being no proof of culpability in any direction, suspicion was the logical guide to precautionary measures.

I regretted the assignment of so valuable a ship as the Montgomery to service in Havana, notwithstanding she was sent to support me in my wishes for naval environment. The Fern was preferred as sufficiently serving the purpose. However, I took up my quarters on board the Montgomery, where I received the kind attentions of Commander Converse.

The first night of the Montgomery in port was marked by a ludicrous incident -ludicrous in the termination, although rather serious in its first stage of development. About 8 P. M. Commander Converse and I had decided to go in company to make a visit of courtesy to the members of the court of inquiry on board the Mangrove The gig had been called away when Commander Converse informed me that a most remarkable tapping sound had been reported from the lower forward compartments of the ship, but could not be precisely located. We were heading to the eastward, broadside to broadside with the Vizcaya, which was on our port beam and very near. We resolved to investigate. Continued reports were demanded. The sound grew in distinctness; there was a regular tapping like that of an electrical transmitter. I recommended that the beats be timed. They were two hundred and forty a minute - a multiple of sixty; therefore, clockwork. That was serious. The crew, being forward, did not like the appearance of things: they did not mind square fighting, but clockwork under the keel was not to their liking. There were some of the survivors of the Maine on board, including the captain. I called for more reports, and directed that some one's ear be applied to the riding-cable, and that a boat be sent to listen at the mooring-buoy, to note if the sound was transmitted through the water. The sound grew in volume, and could be located under a port compartment, well forward. A boat was sent outside to probe with an oar. Nothing was discovered. The bounds of patience were no longer conterminous with the limits of international courtesy, so the bottom of the ship was swept with a rope by means of boats. Other boats were sent to ride at the extreme ends of the lower booms by way of patrol.

I lost my temper, and remarked that one might get as well used to blowing up as to hanging, but once was enough. The tapping never ceased, but began to draw slowly aft. It was reported as most distinct at the port gangway, then was heard most clearly in the port shaft-alley, which was abaft the gangway. Here was the suggestion of a solution. The Montgomery's heading was noted: she was slowly swinging, head to the southward; so was the Vizcaya. A man was sent to note if the sound continued in the forward compartment. It had ceased. The cause was clear: the sound had continued to be most audible in that part of the Montgomery that was nearest the Vizcaya, as the vessels swung at their moorings. It came from the Vizcaya through the water. Commander Converse and I had heroically resolved to remain on board and take our chances. We remained on board, but not heroically. A day or two afterward, when Captain Eulate came on board, we told him of our "scare," to our mutual amusement. He said that the number of beats a minute showed that the sound came from his dynamo or from his circulating-pump.

I have already mentioned that the Spanish men-of-war were vigilant in certain directions as to themselves and not to the Montgomery. My orders to make a friendly visit had not been countermanded. I lived up to them, to the best of my ability, but the situation was daily growing more tense. Immutable law seemed to be impelling Spain and the United States toward war. While abhorring war, as causing more severe and sustained suffering among women and children than among combatant men, I grew gradually into such a condition of mind that I, in common with many of my fellow-countrymen, was not averse to war with Spain.

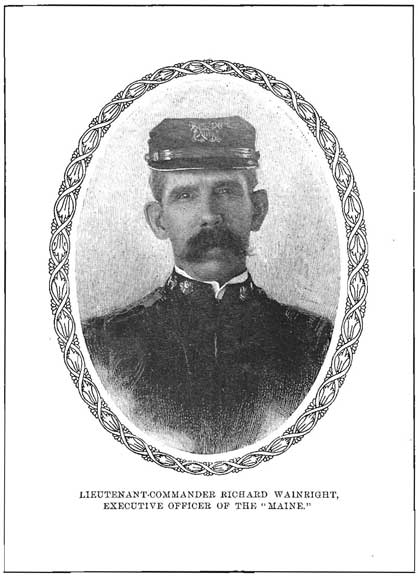

During the latter part of the visit of the Montgomery I believed that her presence in Havana "was no longer desirable. Unless she was protected from without, she was unnecessarily risked. The presence in the harbor of the Vizcaya and the Oquendo offset any moral effect that could be produced by a single United States war-vessel. It was then my opinion that no United States naval force should be employed at Havana unless aggressively, and outside the harbor. It had become impossible for the United States to fly its flag in security for the protection of its citizens. In that connection one could well "remember the Maine." I recommended that the Montgomery be ordered away; she was relieved by the Fern on March I 7, and Lieutenant-Commander Wainwright and I transferred ourselves to the Fern.

It was not my habit at Havana to court serious conversation as to Spanish policies, but, naturally, the views of people of different shades of opinion came to me. Intelligent Cubans declared that Spain desired war with the United States as the most honorable way of relinquishing Cuba. They said that Spain had been preparing for the former event for two years, and pointed to the strong fortifications on the seafront and the absence of fortifications on the land side of the city. A Cuban lawyer of the highest standing, who was closely connected with the politics of the island, and who was willing to accept some degree of Spanish sovereignty, asserted to me that Spain would fight without regard to consequences; that she would fight even though 'she knew that she would be defeated. He appeared to base his belief chiefly on the character of the Spanish people. I was always very cautious as to expressing any opinions of my own. I received views without giving them. In reply to annexation sentiments, it was my custom to say that annexation was not a public question in the United States.

Soon after the destruction of the Maine, a gentleman came to me in the Hotel Inglaterra and tendered me a letter of sympathy from General Maximo Gomez, commander-in-chief of the Cuban army. When the letter was read I expressed my gratitude for the sentiments of General Gomez and accepted them, but asked that the delivery of the letter be deferred until my departure from Havana. It was delivered as requested.

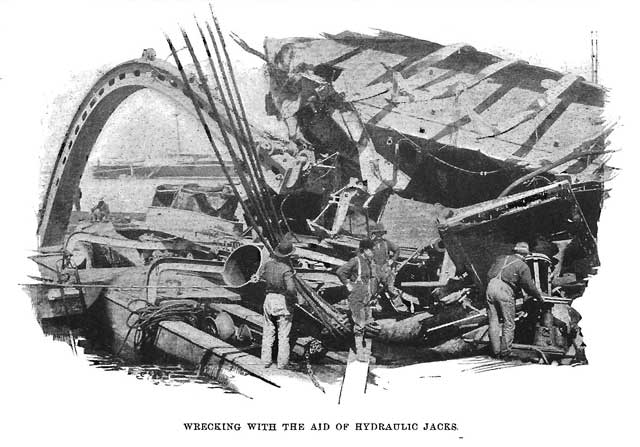

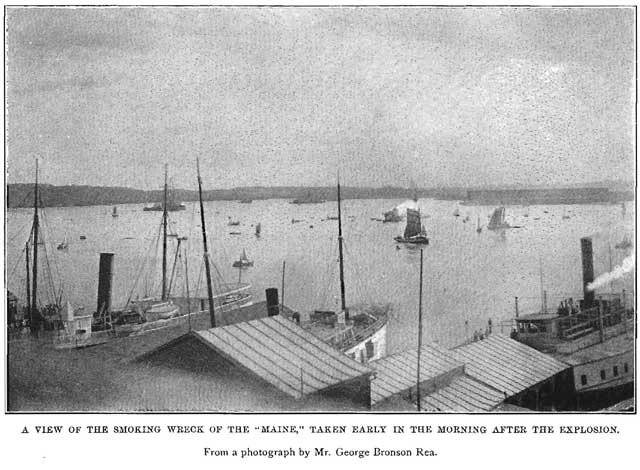

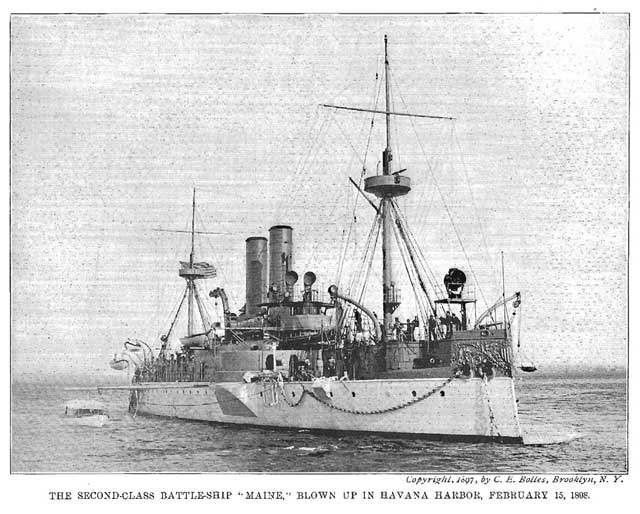

The Maine sank in from five and a half to six fathoms of water, and day by day settled in the mud until the poop-deck was about four feet under water. The first matter to engross the attention of the government and of the officers of the vessel was the care of the wounded, the recovery and burial of the dead, and the circulation of information among the relatives of the officers and crew. Next followed the question of wrecking the vessel. Her value when she arrived at Havana, with everything on board, was about five million dollars. Even a casual inspection of the wreck made it clear that little could be done beyond investigation and the recovery of the dead, except by the employment of the means of a wrecking company. The Mangrove removed certain parts of the armament and equipment, and navy divers were sent from the fleet at Key West to do the preliminary work of searching the wreck. Every naval vessel of large size is provided with a diving outfit and has one or more men trained to dive in armor. The government promptly began negotiations with wrecking organizations, and, as soon as these negotiations took form, Lieutenant-Commander Wainwright was put in charge of the wrecking operations and represented the government in dealing with the wrecking companies. Thereafter he was daily on or about the wreck, at great risk to his health.

At first, bodies were found almost from hour to hour, and were buried as soon as prepared for burial. It was a sad sight at the Machina landing, where bodies were to be seen in the water alongside the sea-wall at all times. To relieve the public eye of this condition of affairs, a large lighter was obtained and anchored near the wreck. On its deck there was always a great pile of burial-cases. To this lighter all bodies were then taken as soon as recovered, and after being prepared for burial, were at first taken to the Colon Cemetery, and toward the last to Key West; in the latter case they were generally carried by the Coast Survey steamer Bache, commanded by Lieutenant-Commander William J. Batnette, U. S. N.

The work of the naval divers, chiefly a work of investigation, occupied about five weeks, and was commonly directed at the zone of explosion, down in the forward part of the wreck. The water of Havana harbor, although filthy, is not so bad in winter as in summer. Our men went down willingly and did excellent service. After each diver had completed his labors for the day he was thoroughly washed with disinfectants. Everything taken from the wreck, except articles of unwieldy size, was plunged into a disinfecting solution. It was recommended by Surgeon Heneberger of the Maine, after conference with Surgeon Brunner of the United States Marine Hospital Service and others, that no article of textile fabric should be used on recovery, but that all should either be burned or given to the acclimated poor of Havana. This recommendation was adopted, and the survivors of the Maine lost all of their clothing. Assistant Surgeon Spear was in charge of the disinfecting processes.

February 19 was an eventful day. The Bache had arrived with divers the day before, but this day the Olivette brought more divers and further outfits. Ensign Frank H. Brumby and Gunner Charles Morgan arrived from the fleet to assist at the wreck. I sent the following telegram to the Navy Department:

One hundred and twenty-five coffins, containing one hundred and twenty-five dead, now buried; nine ready for burial to-morrow

And the following telegram was received by General Lee from the Department of State at Washington:

The government of the United States has already begun an investigation as to the causes of the disaster to the Maine, through officers of the navy specially appointed for that purpose, which will proceed independently.

The government will afford every facility it can to the Spanish authorities in whatever investigation they may see fit to make upon their part.

This despatch disposed of the question of joint investigation. This day funeral services were held at the cathedral over the remains of the Spanish colonel Ruiz, who had been killed in December by order of an insurgent colonel. I desired to attend the funeral with General Lee, in recognition of the public demonstration of sympathy for our dead made by the Spaniards, but reluctantly abandoned my intention because I had no suitable garments to wear. Convention is strictly drawn by the Spaniards in regard to funerals, and one must wear uniform or civil-ian's evening dress; I had neither.

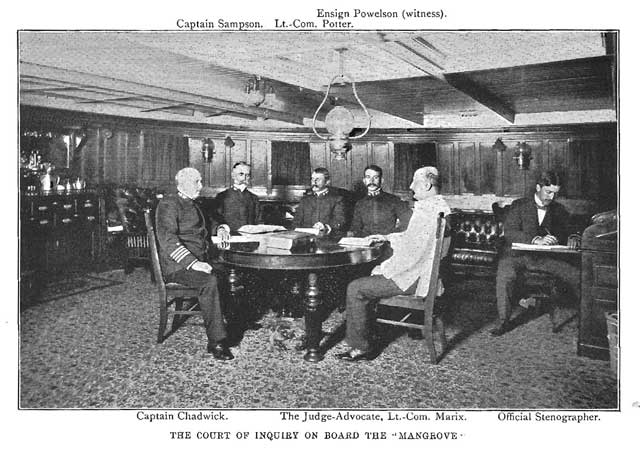

On the 21 st the Mangrove returned from Key West, bringing the members of the court of inquiry, and the court convened on board that vessel. I was the first witness. The court was composed of Captain William. T. Sampson, at that time in command of the battle-ship Iozaa, Captain French E. Chadwick, captain of the flagship New York/and Lieutenant-Commander William P. Potter, executive officer of the New York. The judge-advocate was Lieutenant Commander Adolph Marix, who has already been mentioned as having been at one time executive officer of the Maine. It was a court which inspired confidence. All the members were scholarly men. Admiral Sampson had been at the head of the torpedo station, superintendent of the Naval Academy, and chief of the Bureau of Ordnance. Captain Chadwick had been United States naval attache at London, and chief of the Bureau of Equipment. Lieutenant- Commander Potter had held various positions of importance, especially at the Naval Academy. Lieutenant-Commander Marix knew the structure of the Maine and her organization in every detail; in fact, under a former commanding officer, Captain Arent S. Crowninshield (now chief of the Bureau of Navigation of the Navy Department), he organized the crew of the vessel. He is a highly intelligent, active, and decisive officer. As commanding officer of the Maine at the time of her destruction, I was, in a measure, under fire by the court. The constitution of the court pleased me greatly. I desired to have the facts investigated, not only on their merits, but in a way to be convincing to the public, and I was sure that this court of inquiry would deal with the case exhaustively.

On the same day Commander Peral of the Spanish court of inquiry visited the Mangrove while I was on board, and conversed on various matters. I had already provided him with plans of the Maine, in order that he might be prepared to pursue his independent investigation without loss of time. General Lee informed General Blanco of the expected arrival of wrecking vessels, and no obstacle was put in the way of prosecuting the wrecking work.

During the day various articles were recovered from my cabins: the silverware presented to the vessel by the State of Maine, my bicycle, a typewriting machine, etc. The after-superstructure, in which were my cabins, was the only part of the vessel which was easily accessible to the divers. Below that all was confusion. Everything that was buoyant, including mattresses and furniture, had risen to the ceiling, blocking the hatches. There was some comment as to the recovery of my bicycle. I presume it was in the way of the diver, and he got rid of it by passing it out; or he may have intended to do me a kindness. It was ruined for riding, of course. But I find I have omitted to mention that certain articles of greater importance were recovered. The first work done by the divers was to secure these articles.

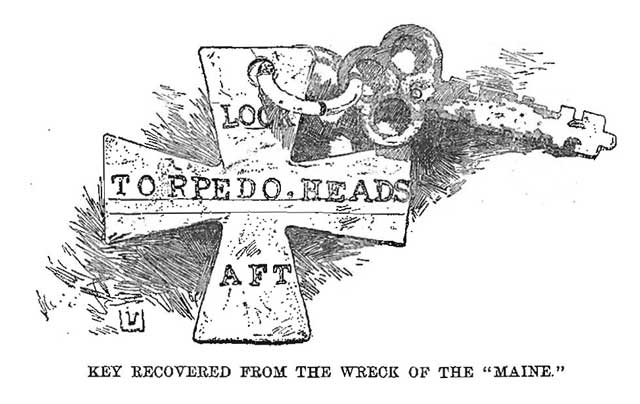

My earliest effort by means of the divers was to secure the navy cipher code and the signal books. In this we were successful. Next the magazine and shell-room keys were sought. They had hung at the foot of my bunk, on hooks, near the ceiling. At the first attempt the diver failed to get them. His failure gave me more of a shock than the explosion itself. A missing key might have meant that a magazine had been entered against my knowledge, or that some diver had been down at night and secured the key. It was a case of treachery on board or of an invitation to war. Lieutenant-Commander Wainwright questioned the diver very closely, and concluded that he had groped about the head of my bunk instead of the foot; so he was sent down again, with repeated instructions and descriptions. This time he brought up the keys, which were in their bags. It appears that the mattress of the bunk had been carried upward by its buoyancy and had lifted the bags off the hooks. They were found just on top of the mattress, immediately above the hooks on which they had hung. The navigator, who was also ordnance officer, found that the key of every magazine and shell-room, including all spare keys, had been recovered. My relief was very great.

The next effort was to recover my private correspondence with General Lee, which I kept in a locked drawer in the bureau of my state-room. There would have been no harm, perhaps, in exhibiting these letters, but they contained an offhand correspondence; therefore I preferred that they should be recovered. In groping within this drawer, the diver got all he could take in his hands, for he could see nothing. He came to the surface with the papers, my watch, and my decoration of the Red Eagle of Prussia, which had been given me by Emperor William I of Germany, in consideration of my deep-sea inventions, and a gold medal which had been awarded me by the International Fisheries Exhibition in London for the same inventions. The latter had been exhibited by the United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries, or by the Smithsonian Institution, I have forgotten which. The decoration and the watch had associations not without public relation, and I may be pardoned for a digression, to state why they were of special value to me.

The decoration had been conferred on me after six years' hard work in deep-sea invention and investigation, in which I had given the United States government freely all of my inventions. The first tangible recognition that I had received from any source came from the Emperor of Germany, through the German minister, the State Department, and the Navy Department. The Constitution of the United States requires an act of Congress to enable any United States official to receive a decoration or present from any foreign potentate or power. The first public recognition of my work from my own country was a prompt adverse report from the Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs when the question of allowing me to accept the decoration came up in Congress. This was disappointing, especially as the German minister expressed concern; but, through the courtesy of certain senators, the report was referred back to the committee for reconsideration, and 1- was finally allowed to receive the decoration. The inventions were developed between the years 1874 and 1878, while I had command of the Coast Survey steamer Blake, engaged in deep-sea exploration for my own government, part of the time in association with Professor Alexander Agassiz. The Blake was afterward exhibited at the Columbian Exposition at Chicago. The principal part of her outfit on that occasion consisted of my inventions or adaptations. The judge in the class under which the inventions came was Captain Concas of the Spanish navy, whom I had never met. He recommended me personally for an award, but when the question was considered by the authorities at the exposition, it was decided that the government, being the exhibitor, should get the award, and the government got it. A high privilege of the nautical man, high or low, here or there, is to grumble away his grievances. Since it can probably be shown that my inventions or fittings have saved the United States government more than one hundred thousand dollars, assuming that it would have done, without their help, the same work that it has done with them, it may be claimed that I am exercising my privilege with more than ordinary foundation.

My watch was not without marine history. I t had been down in salt water three times: once in Japan, many years ago, and the second time in Cuba, about 1878. The second submergence occurred while I was in command of the Coast Survey steamer Blake, engaged in deep-sea exploration in the Gulf of Mexico. Professor Alexander Agassiz was then associated with me for the dredging work which was made a specialty that season. The Blake had been to Havana, where she had obtained authority from the captain-general to enter Bahia Honda, about forty-five miles west of Havana. It was not a port of entry. We were informed that directions had been given there to afford us every facility for the prosecution of the scientific work in which we were engaged. One afternoon, while off Bahia Honda, our steel dredge-rope fouled in the machinery and needed splicing, a tedious operation, suggesting an anchorage in port. It was also desired to enter for the purpose of obtaining, if possible, a pilot for the Colorado Reefs, to the westward, reefs which have never been properly surveyed. During the day a Spanish official boarded the Blake, acting under directions from Havana, and offered to send us a pilot if we should make a signal for that purpose. When it was decided, rather late in the day, to enter the port, the usual signal for a pilot was made. I could not enter without one, because it was too late in the day to discern ~/ -the-channel clearly from the deck, and I had not the necessary charts and books to inform myself

A boat under the Spanish flag put,off promptly from the Spanish fort, and one of her people presented himself as a pilot. In several minutes after his acceptance he grounded the Blake badly, on hard rock bottom, half a mile from shore. A few dayss afterward a gale came on, and the sea made quickly. We were on a lee shore. Officers and crew, excepting a few of us, were landed at the fort. By eight o'clock the sea was beating heavily against the vessel, and she was pounding hard. The pipes in her engine-room began to crack, and there were indications that she would soon go to pieces. I then ordered that the joint of the Kingston valve be opened, that the water might enter the vessel and fill her up to the outside level. She was flooded, and her buoyancy being destroyed thereby, she ceased to pound. Then the rest of us abandoned her for the night. Afterward, during the efforts to get her off, a tugboat from Havana, with an immense hawser made fast to the Blake, suddenly surged on the hawser. It flew violently upward and quivered under great tension. I was then almost exactly under it. Believing that when the reaction took place and the hawser descended it would kill me and the single man in the dinghy with me, I shouted to him to get overboard. I myself jumped, with the result that my watch was filled with salt water. The Blake was afterward floated, and completed a good season's work. The Spaniards had not thought that we could save the vessel. I asked the superintendent of the Coast Survey for a board or court of inquiry. He replied by cable: "No court of inquiry necessary: hearty thanks and congratulations to yourself, officers, and crew for saving the Blake."

It was ascertained that the man sent to pilot us in was a common boatman who had only recently arrived from Santiago de Cuba. He knew absolutely nothing of the channel into Bahia Honda. There were certain vexatious incidents connected with that case. The day after the grounding of the Blake, a Spanish naval officer, under orders from the Spanish admiral at Havana, arrived at Bahia Honda on board an American merchant steamer, to make offer of assistance. He was informed of our needs, whereupon he returned to Havana. Nothing at all was done by the Spaniards for our relief until Professor Agassiz went to Havana, when, by extraordinary efforts, he managed to get from the navy-yard an anchor and a hawser. No apology or expression of regret for the grounding of the vessel was received, and on the night of the grounding, when I sent an officer ashore to a telegraph office about six miles away, with a report to the superintendent of the Coast Survey that I had been grounded by a pilot, the censorship was applied to my despatch, and I was not allowed to telegraph that there was a pilot on board, for the reason, as given by the Spaniards, that the man sent was not a pilot. On that occasion, also, there was an exhibition of courtesy. The governor of the province visited the ship, and the captain of the port, or the equivalent official, was almost constant in his attendance on the vessel during the daytime, as a matter of either courtesy or observation. He gave us no assistance except to advise us to get ashore as soon as a gale came on. He said the sea would make very rapidly. It is only fair to say that there was a fete at Havana during the period stated, which may have interfered with measures which otherwise might have been taken for our relief. A short time thereafter a Spanish man-of-war met with disaster off our coast; her people, as I now remember the case, were rescued by a United States revenue cutter, and were carefully cared for on board the receiving-ship at New York.

I had in view the Bahia Honda censorship when I wrote "suspend opinion.," instead of "suspend judgement," in my Havana despatch.

When I took command of the St. Paul, engaged in the war between Spain and the United States, I thought it unwise again to risk that watch in Cuban waters, so I left it at home, and during the war wore a very cheap one. This recital is hardly pertinent to my narrative of the loss of the Maine, but I have many times been asked to state the circumstances connected with the submergence of my watch the first time in Cuba.

To return to the wreck of the Maine, I find that, up to the night of February 21, one hundred and forty-three bodies had been recovered from the wreck and the harbor. On this day Congress passed a joint resolution appropriating two hundred thousand dollars for wrecking purposes on the Maine. The terms of the joint resolution were as follows:

That the Secretary of the Navy be and he is hereby authorized to engage the services of a wrecking company or companies having proper facilities for the prompt and efficient performance of submarine work for the purpose of recovering the remains of officers and men lost on the United States steamer Maine, and of saving the vessel or such parts thereof, and so much of her stores, guns, material and equipment, fittings and appurtenances, as may be practicable; and for this purpose the sum of two hundred thousand dollars, or so much thereof as may be necessary, is hereby appropriated and made immediately available.

With this the following amendment was mcorporated

And for the transportation and burial of the remains of the officers and men, so far as possible.

The Navy Department having signed contracts with the Merritt & Chapman Wrecking Company of New York, and the Boston Towboat Company, the wrecking-tug Right Arm, belonging to the former company, left Key West for Havana. The contract with the companies put them under my directions as to the kind of work to be done. They were required to work at the recovery of bodies as well as to engage in wrecking the vessel. The tug Right Arm, Captain McGee, arrived at Havana on the 23d and began operations on the 24th. She did not remain long. Thereafter the following vessels were employed on the Maine: the steam-tug T. J. Merritt, the sea-barge F. R. Sharp, and the floating derrick Chief, all for the New York company, and the steam-tug Underwriter and barge Lone Star, for the Boston company. The wrecking work on the part of the contractors was in charge of Captain F. R. Sharp, an expert wrecker. During these days we were often shocked by the sight of vultures flying over the wreck or resting on the frames projecting from the ruins of the central superstructure. I sent the following telegram to the Navy Department on the night of the 24th:

Wrecking-tug Right Arm arrived yesterday. Begins work to-day. Much encumbering metal must be blasted away in detail. Navy divers down aft seven days, forward four days. Bodies of Jenkins and Merritt not found. Two unidentified bodies of crew found yesterday.

After-compartments filled with detached, broken, and buoyant furniture and fittings; mud and confusion. Spanish authorities continue offers of assistance, and care for wounded and dead. Everything that goes from wreck to United States should be disinfected. Wrecking company should provide for this.

Surgeon of Maine, after consultation with others, recommended that all bedding and clothing should be abandoned. Might go to acclimated poor. Useless fittings and equipment . might be towed to sea and thrown overboard. Will take all immediate responsibility, but invite department's wishes. Shall old metal of superstructure and the like be saved Friends of dead should understand that we are in the tropics. Chaplain Chidwick charged with all matters relative to dead. His conduct is beyond praise. Don't know what reports are being printed, but the intensely active representatives of press here have been very considerate of me and my position.(2)

The Secretary of the Navy approved my recommendations and authorized me to use my own judgment.

United States Senator Redfield Proctor arrived at Havana on board the Olivette, from Key West, on the 25ith, I met him frequently during his' visit, which was wholly occupied in a personal investigation of the condition of affairs in the island. His speech in the Senate relative to Cuban affairs is well remembered for its great effect on the public mind in the United States. Afterward a party of United States senators and members of Congress visited Havana on board a private yacht, with the same object in view as that which inspired the visit of Senator Proctor. This party consisted of Senator Money of Mississippi, Senator Thurston of Nebraska, Representative Cummings of New York, and Representative W. A. Smith of Michigan. They were accompanied by other gentlemen and by several ladies, including Mrs. Thurston. The party soon left for Matanzas, to see the condition of things in the neighborhood of that city. We were greatly shocked to learn that Mrs. Thurston, who had visited the Montgomery apparently in good health and spirits while in Havana, had died suddenly on board the yacht in the harbor of Matanzas.

During this period the Bache was occasionally carrying wounded to Tortugas. The slow recovery of bodies and the organization of our work made it possible by the 28th to send bodies to Key West for burial, and the Bache was employed for this sad service. On the 28th the Bache left for Tortugas with five wounded men. They were sent to Tortugas to forestall a quarantine at Key West because of the unfavorable reputation of the Havana hospitals. On this trip she carried one unrecognized body to Key West for burial. This was the first body that was buried in our own soil.

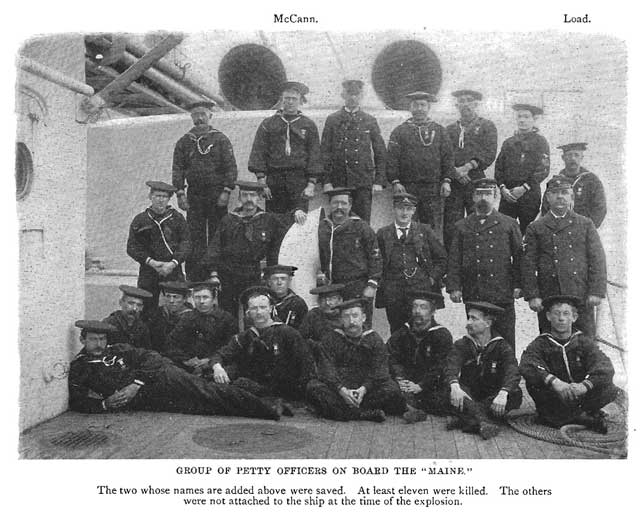

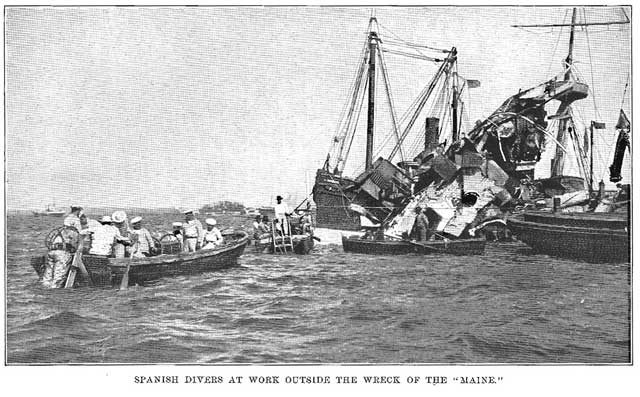

On March 2, the day after the arrival of the Vizcaya, the Spanish divers made their first descent. They continued their work almost daily until March 19, commonly with only one diver down at a time, but occasionally with two. Their time spent in diving aggregated two days twenty two hours and ten minutes for a single diver - a fair amount, but not comparable with the time occupied by the United States divers. The Spaniards worked chiefly from a position outside the ship, forward on the starboard side. To us it appeared that they devoted considerable attention to the locality outside of the Maine. Their operations were quite distinct from ours; each party pursued its own course undisturbed by the other.

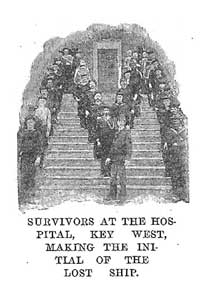

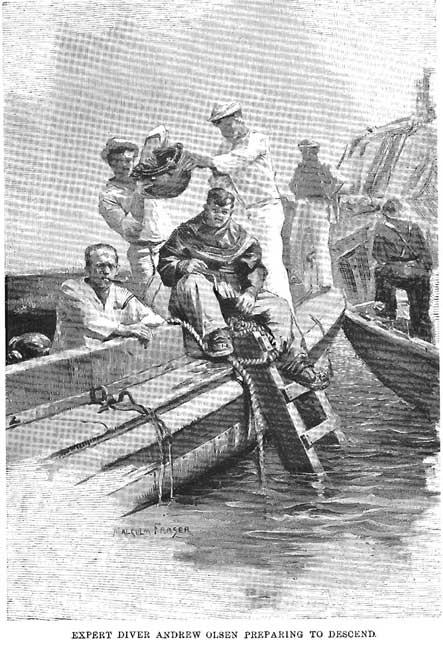

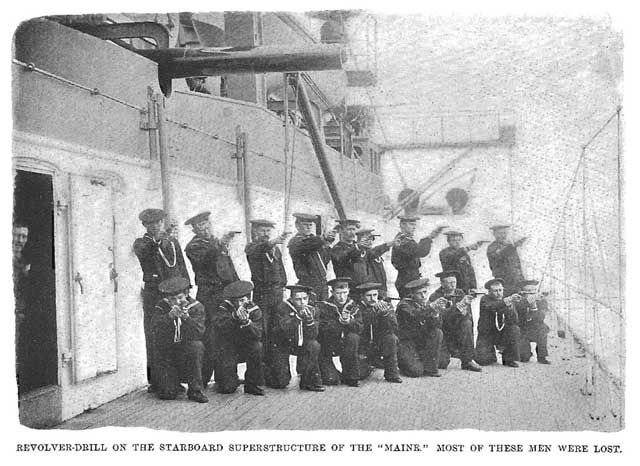

The naval divers of the United States who gave testimony were Gunner Charles Morgan of the New York, Chief Gunner's Mate Andrew Olsen and Gunner's Mate Thomas Smith of the Iowa, Gunner's Mates W. H. F. Schluter and Carl Rundquist of the New York, and Seaman . Martin Redan of the Maine. For the wrecking companies the divers were Captain John Haggerty and William H. Dwyer, both men of great diving experience. I think nearly all the young officers of the line of the navy associated with me at that time begged to be allowed to dive in armor at times when points involving close decision came up. Ensign Charles S. Bookwalter, Ensign Powelson, and Naval Cadet Holdencertainly offered their services, and I think Naval Cadet Cluverius also.

I found Captain Pedro del Peral of the Spanish navy, who was in charge of the Spanish investigation, a highly intelligent and most agreeable officer. His relations with me were always pleasant. It did not appear to us United States officers that the Spanish diving work was as thorough as our own. Doubtless the Spanish commission or court of instruction had its own way of doing things, without respect to our views; nevertheless, the Spanish official investigation lacked the scientific and sifting quality that characterized that of the United States. (3)

The United States court of inquiry took up thoroughly the question of explosion from the interior, and was unsparing of individuals in its investigation. It endeavored to ascertain if mistakes had been made, if there was laxity in any direction pointing to culpability on the part of those on board, and if the conditions of duty, stowage, and routine favored an interior explosion. It would have been very gratifying to me, and doubtless to other survivors of the Maine, had the Spanish commission made an investigation of the same searching and exhaustive character relative to matters exterior to the vessel. On the Spanish side we find no investigation as to the existence or non-existence of mines in the harbor, nor as to the possible existence at Havana of explosives or torpedoes that could have been used against the Maine. Although the advantages for investigation as to interior causes were on the American side, they were as decidedly on the Spanish side in all that related to matters exterior to the Maine.

The Spanish report as published in the document already referred to was submitted to the United States government by the Spanish minister at Washington as the "full testimony in the inquiry." On page 596 of the document is published a preliminary report relating to the cause of the disaster. The preliminary report is dated in the printed United States document April 20, which is an error, my authority for this statement being the Department of State. The actual date of the report is February 20, only five days after the explosion, and one day before the United States court met at Havana. The report finds, "although in reserved character," that the explosion was not caused by an accident exterior to the Maine.

The following is a copy of the report:

Thinking it proper, in view of the importance of the unfortunate accident occurring to the North American ironclad Maine, to anticipate, although in reserved character, something of that which in brief will form part of the opinion of the fiscal [attorney-general] upon that which I undersign, and in case your Excellency should think it opportune and proper to inform the government of her Majesty thereof, I have the honor to express to your Excellency that from the judicial proceedings up to to-day in the matter, with the investigation with which you charged me immediately after the occurrence of the catastrophe, it is disclosed in conclusive manner that the explosion was not caused by any accident exterior to the boat, and that the aid lent by our officers and marines was brought about with true interest by all and in a heroic manner by some.

It alone remains to terminate this despatch that when the court can hear the testimony of the crew of the Maine, and make investigation of its interior, some light may be attained to deduce, if it is possible, the true original cause of the event produced in the interior of the ship. God guard your Excellency many years.

At a certain stage after the court had begun its investigation it appeared to the members, and also to General Lee, that there was no longer any objection to the Spanish authorities beginning their independent investigation by means of diving in and about the wreck. It was suggested that I invite the Spanish authorities to begin operations. I declined, although willing to have them proceed. At that time I had full control of the Maine, and remembered that the Spanish authorities had previously assumed a dictatorial position in reference to my command. I therefore declined to move in the matter except with the express authorization of the United States government, thinking it a very essential point that no access.to the Maine should be given in advance of that authorization. The question was referred, as desired; the authority was given me, and I was content, because it was my sincere belief that the Spanish government had at least a strong moral right to investigate the wreck of the Maine.

The Spanish investigation was ordered immediately after the explosion. In fact, the Spanish commission began taking testimony one hour thereafter, the first witness being Ensign Manuel Tamayo, who was officer of the deck of the Alfonso XII at the time of the explosion. In my conversation with Spanish officers, in which frankness seemed to be the rule, they placed great stress on certain phenomena attending the explosion, such, for example, as the column of flame or water thrown up, the concussion on shore, and on board the ships in the harbor, the waves propagated in the harbor, the apparent absence of dead fish in the water after the explosion, etc., all of which were very proper to be considered for what they were worth. The United States court of inquiry took up these points also, but the general tenor of its investigation was much more rigid. As to the number of fish killed, it was said by certain people that there were not many fish in the harbor of Havana, even in the daytime, and that at night they took to the sea outside; but it is believed that no great weight was attached to this statement on our side. Our own officers knew that, of the many fish commonly thrown to the surface by the explosion of a submarine torpedo, most of them are merely stunned, and if left undisturbed will swim away in a short time.

As already said, General Blanco had been promised that no American newspaper correspondents should be permitted to enter into any investigation of the Maine. His request was hardly necessary, but I saw that his wishes were fulfilled. The ubiquitous American newspaper correspondent could not be denied, however. It caused our officers some amusement to see occasionally a certain newspaper .correspondent sitting in the stern of the Spanish divers' boat while it was working on the wreck. I made no objection. The incident put me on the better side of any contention that might arise, and it was not believed that the correspondent would gather much information worthy of publication. This particular correspondent afterward said that the Spaniards knew that he was an American, but allowed him to make his visits, believing that he was actuated only by a purely scientific spirit of observation.

It was fortunate that Ensign Wilfred V. N. Powelson was serving on board the Fern. His services to the court were of inestimable value. Ensign Powelson had been the head man of his class at the Naval Academy. After graduation and a short service in the line he began a course of study in naval architecture at Glasgow, Scotland, with a view of entering the Corps of Naval Constructors. At the end of the first year in Glasgow he decided to remain a line officer, whereupon he was allowed to discontinue the course and resume his previous duties. Naval architecture and naval construction were taught .at the United States Naval Academy in fair degree also. The scientific tendencies of Ensign Powelson and his studies at the Naval Academy and at Glasgow gave him a special fitness for the investigation of the wreck, which he pursued with unceasing interest and care. Under the direction of Lieutenant-Commander Wainwright, he ordered, in the largest degree, the details of the operations of the divers. His system was admirable. He would have the divers measure different parts of the submerged structural features of the vessel, and, in case of doubt, would have more than one diver take measurements of the same parts. Then he would refer these measurements to the detailed drawings of the Maine, which we had in abundance. In this way he would show beyond question the precise position that the several parts had occupied in the structure of the Maine. To illustrate his methods: If a piece of the bottom plating of the vessel had a certain longitudinal measurement between frames, he would show that the piece must have come between certain frames. By measuring the transverse width of the plate and other dimensions, he would demonstrate that it could have come only from a certain position between those frames. If there was a manhole plate, he would show that it could be only a certain manhole plate, the precise position of which when intact he could refer to the drawing. He would question the divers and formulate their reports. Then his testimony before the court, verified by the testimony of the divers, would go on the record of the court for consideration. Through this careful method of investigation it was ascertained that at Frame 17 the bottom plating of the ship had been forced up so as to be, four feet above the surface of the water, or thirty-four feet above where it would have been had the ship sunk uninjured; also that the vertical and flat keels had been similarly forced up in a way that could have been produced only by a mine exploded under the bottom of the ship.

When the court had concluded its labors at Havana, I desired to relieve myself of the neutral condition of mind in which I had thought it proper to continue while the court's investigation proceeded. There was, naturally, no indication from the court as to the character of its findings. I invited Ensign Powelson to formulate his views as to the initial seat of the explosion, in a written report to me. His testimony before the court of inquiry had been a recitation of details. His report to me embraces his own reasoning and conclusions, and is given in Appendix E. I wished the truth and nothing but the truth, and I wished it as disconnected from my own suspicions and prejudices. Ensign Powelson's report in connection with the testimony of others before the court convinced me that I could accept my own views which had been allowed to lie dormant. I never believed any other theory than that the Maine was blown up from the outside, but I should have surrendered my view to an adverse finding of the court based on adequate ground. The murder of two hundred and fifty sleeping and unoffending men is too great a crime to charge against any man's soul without proof.

The court investigated first the probability of an interior cause. The discipline of the ship and the precautions taken against explosion from the inside, whether fortuitous or as the result of treachery, were subjected to careful inquiry. The testimony, as connected with a possible interior cause, apparently reduced that aspect of the case to the consideration of a single" pocket" coal-bunker on the port side, adjoining the six inch reserve magazine. The counterpart of this bunker on the starboard side was in use on the day of the explosion, and was therefore outside the realm of suspicion. Only the two aftermost boilers of the ship were in use. The pocket bunker which was most seriously in question had been full of coal in a stable condition for three months. Its temperature had been regularly taken, and the temperatures of the magazine adjoining it had been taken every day and recorded. The bunkers were provided with electrical alarms of unusual sensitiveness, the indications of which were recorded on a ringing annunciator near my cabin door. It so happened, fortunately for the investigation, that the bunker in question was the most exposed on its outer surface of all in the ship. It was exposed on three sides. On the deck above the magazine it formed three sides of a passageway which was traversed many times a day, and the hands of officers and men were placed on the sides of the bunker, unconsciously, in passing that way. Certain lounging-places for the crew were bounded by the walls of that bunker. Its temperature was taken on the day of the explosion. In the testimony before the court there seemed to arise hardly a suspicion in any direction pointing to an interior cause, further than that this bunker was full of coal and was, in fact, next to a magazine. A strong point was the fact that the boilers next those forward bunkers had not been active for three months. On the contrary, there were many facts developed which conspired to indicate that the primary explosion was outside the vessel.

No American, so far as I know, appeared before the Spanish court or commission, and no Spaniard before the American court; but a foreigner, a resident of Havana for many years, gave testimony before the latter. According to his own account, this witness must have held the opinion that he was in a country where distasteful people were likely to be murderously dealt with. It is not clear, therefore, why he chose to testify and run into danger. I formed the suspicion that he was a detective, and gave no credence to his unsupported testimony; I doubt that anybody else did.

It seems unlikely that the agency which produced the explosion of the Maine will always remain unknown.. It will be sought with more persistency than has been brought to bear on the investigation of the first landing-place of Columbus, the final resting-place of his remains, or the identity of the" iron mask."

The court of inquiry was obliged to meet in turn both at Key West and Havana, because the Maine's people had been distributed. The Mangrove, with the court aboard, left Havana for Key West on February 26, returned on March 5, and left finally on March I5. It completed its report at Key West on March 2 I, one month after its first sitting at Havana. Its findings are given in Appendix C. On March 28 its report was transmitted to Congress in a message from the President of the United States, which is given in Appendix D. The rapid movement of events toward war with Spain after the reception by Congress of the President's message is a matter of current history; so is the downfall of Spanish colonization through the operations of the United States army and navy.

After the court had completed its work at Havana, the wrecking operations on the Maine, under the direction of Lieutenant-Commander Wainwright (who had as an assistant Naval Cadet Cluverius, a very able and conscientious young officer), became the event of chief interest. Nearly, if not quite, all her guns were recovered, but not those in the turrets. The breech-blocks of the after-turret guns were recovered and saved. I had recommended that bags' of crystal acid be put into the chambers of the turret guns to eat away the tubes, but I doubt that this was done.

The forward half of the Maine was distorted and disintegrated beyond repair. She was hardly worth raising for any practical purpose whatever, but it took time completely to develop this conclusion. Toward the last, the wrecking force having removed all the parts above water that could be detached by ordinary means, Captain Sharp desired to use dynamite, in small charges or in the form of tape, to blast away connecting parts in detail. He requested me to apply to the Spanish officials for authority to import about two hundred pounds of dynamite. I made known . his wishes to General Lee, who reported them to- the Spanish authorities, with a request from me that a place be named where the dynamite might be kept. General Blanco bluntly, even contentiously, refused the request. This virtually reduced the wrecking work to the recovery of armament, equipment, and fittings. The Navy Department then informed me that it did not approve the use of dynamite. The situation, J by that time, was strained beyond relief.

On March 26 al1 of the Ma£ne's officers except Lieutenant-Commander Wainwright were detached and left Havana for Key West by the Oiivette, Wainwright remaining behind to represent the government in connection with the wrecking companies. General Lee, many American newspaper correspondents, and other gentlemen, and a few ladies, came on board to see us off. After a time we were invited into the dining-cabin. Attention was soon demanded by General Lee, who made a short and touching address to me in which he showed much feeling. He and I had worked together so completely in unison during the stress of the great disaster that the breaking of the bond could not but be felt deeply by both of us. He then presented to me, in behalf of the American press correspondents in Havana, a beautiful floral piece which had been brought on board. I replied in a short address, - in which I returned thanks and expressed my appreciation of the kind forbearance that had been shown to me by the gentlemen of the press in Havana. The parting was a solemn one to me, and, I think, to all present. The small American colony which had held together in close sympathy during the whole trying period following the loss of the Maine was now breaking up; and the interruption of friendly relations with Spain was at hand. I was completely taken by surprise by this cordial demonstration of the newspaper correspondents. Since I had been able to do but little for them in their official characters, it pleased me greatly that I had nevertheless won their private regard. I find that it takes a strong effort of moral courage to refer in this way to gentlemen of the press, - one's motive may so easily be misconstrued,- but to one who will try to fancy himself in the position that I occupied at Havana, the gratification that I have expressed, and my desire to express it far more strongly, should be apparent.

On leaving Havana, I disliked exceedingly to have Lieutenant-Commander Wainwright remain behind. My first official act afterward, when I arrived at the Navy Department, was to recommend that he be relieved. He had had a long and difficult tour of duty in connection with the wreck, during which he had borne up nobly. On the day after our departure from Key West, the Bache returned to Havana harbor, with Captain Chadwick, as senior member of a board, in association with Lieutenant-Commanders Cowles and Wainwright, to determine the final disposition that should be made of the wreck. They soon after reported adversely as to further measures. Wrecking operations were therefore abandoned. Lieutenant-Commander Wainwright left Havana about April 5; General Lee and the American citizens, as a body, on April 9. General Lee left on board the Fern, with Lieutenant-Commander Cowles. As the Fern steamed out of the harbor derisive whistles from people on shore were heard.

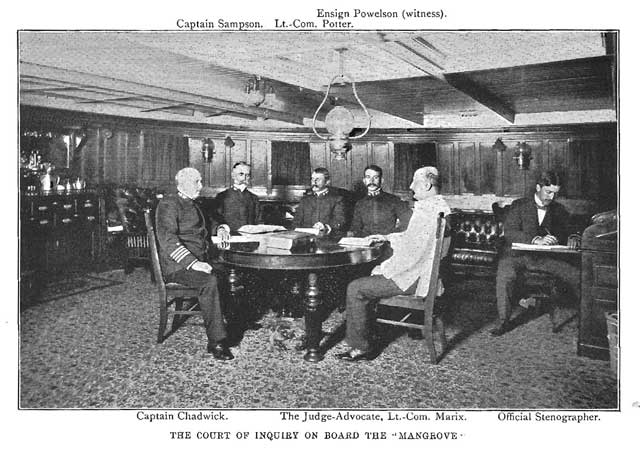

My duties at Havana were confined so specifically to certain features of the situation that I was not personally cognizant of much that was going on about me, and concerning which I regret that I am not better informed. For example, there was much kindness shown by kindhearted people to our men at the hospital at Havana. I remember especially the attentions of Sister Mary Wilberforce and Mr. Charles Carbonell. The Spanish surgeon in charge of the hospital at Havana should not be forgotten; every report that came to me from the hospital showed that he gave our men the very best care to be had, in that institution. The report of the Spanish Court of Instruction shows that helpfulness was wide-spread among the Spaniards. At Key West the wounded were cared for in the hospital at the army barracks and in the marine hospital near the fort. The citizens of Key West were very attentive to the wounded men.

On arriving in Washington, I reported to the Hon. John D. Long, Secretary of the Navy. The Secretary took me to the Executive Mansion, where he presented me to President McKinley, who greeted me cordially and with kind words. My immediate connection with the disaster to the Ma£ne may be said to have ended on the night of April 2, when a reception was given to me at the Arlington Hotel in Washington by the National Geographical Society, of which I am a member; it was under the direction of the president of the society, Professor Alexander Graham Bell, assisted by some of his associates. The reception was attended by the President of the United States, the Vice-President, the Secretary of the Navy, and many distinguished gentlemen, official and private, in Washington at that time. Ladies were present in equal number with the men. I greatly regretted that, through force of adverse circumstances, I was the only representative of the Maine present. Perhaps no more distinctive personal honor has ever been paid by the President of the United States to a naval officer than was shown me that night. My only regret was that it could not, in some way, have found a place on the files of the Navy Department. An officer whose life is spent in the naval service is keenly alive in all matters affecting his official record.

I was deeply disappointed that there was no battle- ship the command of which was vacant. I had hoped for an immediate command of that nature, some vessel at least as large as the Maine, as a mark of the continued confidence of the government, officially and publicly expressed. I mentioned my regret to the President and the Secretary of the Navy. The day after the reception I told the Secretary of the Navy that I withdrew all question as to the size of a command, and was desirous of accepting any command where I could be of service. With great consideration, the secretary soon gave me the command of the auxiliary cruiser St. Paul, which was probably the largest man-of-war ever commanded by anybody. Her displacement was sixteen thousand tons, or four thousand tons more than that of our largest battle-ship, the Iowa. She was under complete man-of-war organization.

As might have been expected, the surviving officers and crew of the Maine were much scattered after their formal detachment from that vessel. Members of the crew, as a rule, were distributed among vessels at Key West. Lieutenant-Commander Wainwright was given command of the Gloucester. He did fine service with that vessel on the south side of Cuba, and, later, on the south side of Porto Rico. The action of the Gloucester with the torpedo-boat destroyers Pluton and Furor is well remembered. Lieutenant Holman was ordered to the torpedo-station at Newport; Lieutenant Hood was first given command of the Hornet, and later was attached to the Topeka >" Lieutenant Jungen was given command of the Wampatuck, Lieutenant Blow commanded the Potomac, and later was attached to the Vulcan. Lieutenant Blandin was attached to the Bureau of Equipment, Navy Department: he died on July r6; Naval Cadets Holden and Cluverius were attached to the Scorpion under the command of Lieutenant-Commander Marix J. Naval Cadet Bronson was attached first to the Scorpz"on and then to the Amphitrite; Naval Cadet Boyd was attached first to the flagship New York and later to the Cushing.

Staff-officers were ordered to service as follow: Dr. Heneberger to the St. Paul, under my command; Paymaster Ray in charge of the navy pay-office, at Baltimore; Chief Engineer Howell to the Newark; Passed Assistant Engineer Bowers to the New York navy-yard; Assistant Engineer Morris to the Columbia; Naval Cadet Washington to the New Orleans; Naval Cadet Crenshaw to the San Francisco, and at the time of this writing he is on board the Texas under my command; Chaplain Chidwick to the Cincinnati; First Lieutenant of Marines Catlin to the St. Loicis , Boatswain Larkin to the League Island "navy-yard; Gunner Hill to the New York navy-yard; Carpenter Helm to the receiving- ship Vermont; Pay-Clerk McCarthy to the Columbia; Sergeant Anthony was transferred to the Detroit, where he served during the war.

While in Washington I was directed to appear before the Committees on Foreign Relations in the Senate and the House. The committees questioned me freely on points tending to amplify the investigation of the court of inquiry. One of the committees. desired to be informed, substantially, if I could attribute the loss of the Maine to any special mechanical agency or to any person or persons. I replied that I had no knowledge that would enable me to form a judgment in those particulars. I was then pressed, formally and informally, as to possibilities instead of probabilities. When the investigation took a hypothetical character, I explained a mechanical means whereby the Maine could have been blown up, and referred to persons who were in a position which would have enabled them to blow her up had they been so inclined. It was well understood on both sides that no charge was made, since no evidence existed. The plan shown was of my own conception. The committee was informed that the watering population of Havana was Spanish, not Cuban; also that there were many Spaniards in Havana who presumably had more or less knowledge of torpedoes and submarine mines, and who could have blown up the Maine had they so desired. This personal phase of the investigation was not pleasant to me, because it did not deal with known actualities, but, beyond doubt, the committee was right in pressing the inquiry as far as it deemed necessary. The loss of the Maine was not a subject of investigation in which the committee was likely to feel unduly inclined to deference toward any persons whatever.

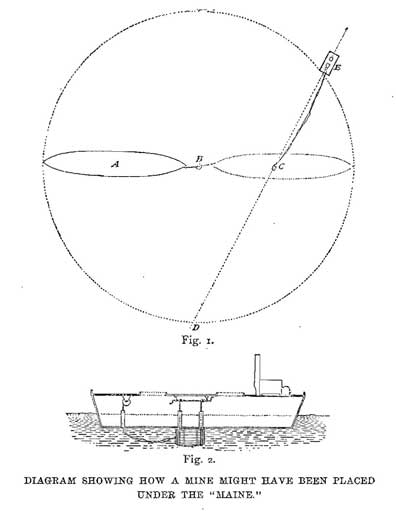

The mechanical plan is shown in Fig. I, on this page. The Maine, A, swinging in a complete circle around the fixed mooring-buoy, B, would have covered progressively every part of the area bounded by the dotted line shown in the diagram. Therefore at some time during her swing she would have been over a mine planted anywhere in that area as at C. To blow her up would have been an easy matter, if a mine could have been so planted without suspicion. It would have been chiefly a question of time to await the favorable moment, and of immunity from suspicion and arrest. Many lighters were moving about in the harbor every day; some passed and re passed the Maine in various directions. Could a lighter, taking advantage of this traffic, have proceeded past the Maine along any route, as DE, crossing the area of danger, and have dropped a mine without detection? It is believed that she could have succeeded, even though the men on lookout on board the Maine had been watching her at the time. The method that I conceive could have been employed was explained by me to Captain Sampson and Commander Converse on board the Montgomery. Each, in turn, had been in charge of the Torpedo School at Newport. They admitted that the plan was feasible, and when I pointed to a lighter passing ahead of the Montgomery, each admitted that if she were" then dropping a mine, according to the plan described, we could not detect her in the act. It was maintained, however, that it would require about twelve persons of different kinds of skill, acting in collusion, to execute the plan in its entirety.

Fig. 2, page 182, represents my idea of such a lighter and of her procedure. Under a decked lighter of large capacity is slung a mine very large, but so loaded that its specific gravity, as a whole, is only slightly greater than that of the harbor water. Let it weigh, say, one hundred pounds in water. It is slung from a tripping- bar within the lighter, the slings passing through tubes which are let into the bottom of the lighter and extend upward above the level of the outside water. Insulated wires lead forward. from the mine and through a similar tube to a· reel mounted within the ·lighter. If a lighter, so prepared, is slowly towed through the water, or preferably driven slowly by a noisy geared engine, of the type seen in Havana, she can drop her mine on ranges, unobserved, as she may choose. The mine being wholly submerged, no wave will be noticed on letting go; the;e will be no jump of the lighter, any more than would be evident were one of her crew to fall overboard. With a heavy lighter there will be no sudden change of speed; at least, this can be provided against by opening the throttle of the engine wider at the right time. When the mine drops, the· electrical wires payout automatically. The lighter goes alongside a wharf or anchors. She may land her wires, if opportunity serves, or at the right moment the explosion is caused electrically on board the lighter. She then leaves her berth, drops her wires elsewhere, and disposes of her fittings.

On board the Maine the greatest watchfulness was observed against measures of this kind; not that I believed we were likely to be blown up, but as a proper precaution in a port of unfriendly feeling. On the day of the explosion, or the day before, I caused ten or twelve reports to be made to me concerning a single lighter that passed and re passed the Maine. She did not pass within what I may call the area of danger, and she was not of a type to have carried out the plan just set forth.

In dwelling on these problematical matters it should not be thought that it is "intended to point to any individual responsibility for the Maine disaster. I shall not break my rule of reserve, but, short of personal accusation, investigation of so horrible a disaster may pursue any promising line of thought, even beyond suspicion and into the domain of abstract possibility.

It cannot be doubted that a large number of the people of the United States have refused to relieve Spain of moral responsibility for the loss of the Maine. In conversation with many Americans, and, notably, with a distinguished citizen who has held high public office at home as well as high diplomatic office abroad, I have gathered points in what the latter gentleman calls an indictment. Since these points indicate public opinion in considerable degree, it may be of interest to set them forth here, especially as they may have guided public action indirectly through individual activity.

Spain, in respect to Cuba, was not friendly to the United States. Havana was heavily fortified on the sea-front, not against Cuba, but, obviously, against the United States. The Maine was not welcome at Havana. Her coming was officially opposed on the ground that it might produce an adverse demonstration. By officials she was treated with outward courtesy; otherwise, she was made to feel that she was unwelcome. She was taken to a., special mooring buoy - a buoy that, according to the testimony given before the United States naval court of inquiry, was apparently reserved for some purpose not known. She was taken to this buoy by an official Spanish pilot, and she was blown up at that buoy by an explosion from the outside. Therefore there must have been a mine under the Maine's berth when she entered the harbor, or a mine must have been planted at her berth after her arrival. In either case, the Maine nity serves, or at the right moment the explosion is caused electrically on board the lighter. She then leaves her berth, drops her wires elsewhere, and disposes of her fittings.

On board the Maine the greatest watchfulness was observed against measures of this kind; not that I believed we were likely to be blown up, but as a proper precaution in a port of unfriendly feeling. On the day of the explosion, or the day before, I caused ten or twelve reports to be made to me concerning a single lighter that passed and re passed the Maine. She did not pass within what I may call the area of danger, and she was not of a type to have carried out the plan just set forth.

In dwelling on these problematical matters it should not be thought that it is intended to point to any individual responsibility for the Maine disaster. I shall not break my rule of reserve, but, short of personal accusation, investigation of so horrible a disaster may pursue any promising line of thought, even beyond suspicion and into the domain of abstract possibility.

It cannot be doubted that a large number of the people of the United States have refused to relieve Spain of moral responsibility for the loss of the Maine. In conversation with many Americans, and, notably, with a distinguished should have been protected by the Spanish government. She was not informed of the existence of a mine at her berth, or cautioned in any wise against danger from mines or torpedoes. In her attitude of initial and reiterated friendship, she was powerless to search her mooring-berth. She was obliged to assume a due sense of responsibility on the part of the Spanish authorities. Yet it has not appeared that they took any measures to guard her. Mining plants for harbor defense, and their electrical connections, are always under the express control of governments, and in charge of a few people who alone have the secret of position and control. Therefore responsibility for accident, or worse, is centralized and specific.